1822 – Charles Babbage (1791-1871) and Ada Augusta, The Countess of Lovelace

Charles Babbage is known as the Father of the modern computer (even though none of

his computers worked or were even constructed in their entirety). He first designed

plans to build, what he called the Automatic Difference Engine. It

was designed to help in the construction of mathematical tables for navigation.

Unfortunately, engineering limitations of his time made it impossible for the

computer to be built. His next project was much

more ambitious.

Charles Babbage is known as the Father of the modern computer (even though none of

his computers worked or were even constructed in their entirety). He first designed

plans to build, what he called the Automatic Difference Engine. It

was designed to help in the construction of mathematical tables for navigation.

Unfortunately, engineering limitations of his time made it impossible for the

computer to be built. His next project was much

more ambitious.

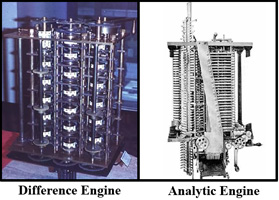

While a professor of mathematics at Cambridge University (where Stephen Hawkin is now),

a position he never actually occupied, he proposed the construction of a machine he called

the Analytic Engine. It was to have a punched card input, a memory unit

(called the store), an arithmetic unit (called the mill),

automatic printout, sequential program control, and 20-place decimal accuracy.

He had actually worked out a plan for a computer 100 years ahead of its time.

Unfortunately it was never completed. It had to wait for manufacturing technology to

catch up to his ideas.

While a professor of mathematics at Cambridge University (where Stephen Hawkin is now),

a position he never actually occupied, he proposed the construction of a machine he called

the Analytic Engine. It was to have a punched card input, a memory unit

(called the store), an arithmetic unit (called the mill),

automatic printout, sequential program control, and 20-place decimal accuracy.

He had actually worked out a plan for a computer 100 years ahead of its time.

Unfortunately it was never completed. It had to wait for manufacturing technology to

catch up to his ideas.

During a nine-month period in 1842-1843, Ada Lovelace translated Italian mathematician Luigi Menabrea's memoir on Charles Babbage's Analytic Engine. With her translation she appended a set of notes which specified in complete detail a method for calculating Bernoulli numbers with the Engine. Historians now recognize this as the world's first computer program and honor her as the first programmer. Too bad she has such an ill-received programming language named after her.

The Story Behind Bill Gates and Microsoft

The Birth of Microsoft

In December of 1974, Paul Allen was on his way to visit Gates when

along the way he stopped to browse the current magazines. What he saw

changed his and Bill Gates's lives forever. On the cover of Popular

Electronics was a picture of the Altair 8080 and the headline "World's

First Microcomputer Kit to Rival Commercial Models." He bought the issue

and rushed over to Gates's dorm room. They both recognized

this as their big opportunity. The two knew that the home computer

market was about to explode and that someone would need to make software

for the new machines. Within a few days, Gates had called MITS (Micro

Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems), the makers of the Altair. He

told the company that he and Allen had developed a BASIC that could be

used on the Altair. This was a lie. They had not even written a line of

code. They had neither an Altair nor the chip that ran the computer. The

MITS company did not know this and was very interested in seeing their

BASIC. So, Gates and Allen began working feverishly on the BASIC they

had promised. The code for the program was left mostly up to Bill Gates

while Paul Allen began working on a way to simulate the Altair with the

schools PDP-10. Eight weeks later, the two felt their program was ready.

Allen was to fly to MITS and show off their creation. The day after

Allen arrived at MITS, it was time to test their BASIC. Entering the

program into the company's Altair was the first time Allen had ever

touched one. If the Altair simulation he designed or any of Gates's code

was faulty, the demonstration would most likely have ended in failure.

This was not the case, and the program worked perfectly the first time.

MITS arranged a deal with Gates and Allen to buy the rights to their

BASIC. Gates was convinced that the software market had been born.

Within a year, Bill Gates had dropped out of Harvard and Microsoft was

formed.